Concept

Worldmaking

by Adam Budak

Worlds like words multiply in the narrative of lives we conduct. One after another, and the one next to it, they proliferate in an organic process of symbiosis and growth. American philosopher, Nelson Goodman underlines the world’s collective self-referentiality, its interdependency and plurality: “If I ask about the world, you can offer to tell me how it is under one or more frames of reference; but if I insist that you tell me how it is apart from all frames, what can you say?” Nelson sees the world as a fabric of interwoven narratives; our role is to retell those narratives. To find the strategy - the way to do it - is what constitutes and determines our task: “We are confined to ways of describing whatever is described. Our universe, so to speak, consists of these ways rather than of a world or of worlds. (…) The many stuffs - matter, energy, waves, phenomena - that worlds are made of are made along with the worlds. But made from what? Not from nothing, after all, but from other worlds. Worldmaking as we know it always starts from worlds already on hand; the making is remaking.”1

Such is a paramount premise of the 7th Biennale Gherdëina: to research and to challenge our ability to contribute to an active process of the world’s continuous (re)making while the world we inhabit finds itself at its apparent limit: in a critical precarious moment of a sociopolitical turmoil, an ethical vacuum and an immunological crisis. The principle of responsibility and care, as well as civic responsiveness and a humility linked to it, come forth as agencies of our daily poiesis, defining the urgency to act and engage. We are in this together, a chant frequently uttered during the recent months of the pandemic limbo, reminds the founding statement of the philosopher Rosi Braidotti’s politics of affirmation. We are this world’s participants, its tender narrators2 and the passerby3, listening to the poets, the Shelleyian “unacknowledged legislators of the world”. Ultimately, we are the interpreters of this world and its vast fields of land and thought, both real and imaginary. In this together.

The 7th Biennale Gherdëina’s main title - a breath? - a name? embraces a line from a poet of “the world’s unreadability”, the most important German-language authors of his time Paul Celan (1920-1970).4 French philosopher Jacques Derrida analyses the poet’s poetics and politics of witnessing, describing Celan as a poet of singularity, of solitude, and of a secret encounter. The poet bears witness and “the poem speaks, even if none of its references is intelligible, none apart from the Other, the one to whom the poem addresses itself and to whom it speaks in saying that it speaks to it. Even if it does not reach the Other, at least it calls to it. Address takes place.”5 The act of address, of naming, sets up an ethical stance. Derrida voices the call to responsibility on Celan’s line The world is gone. I must carry you (Die Welt ist fort, ich muss dich tragen), following French philosopher Maurice Blanchot’s elaboration of responsibility as a paradox of subjectivity which involves a withdrawal and accountability: “My responsibility for the Other presupposes an overturning such that it can only be marked by a change in the status of ‘me,’ a change in time and perhaps in language. Responsibility, which withdraws me from my order - perhaps from all orders and from order itself - responsibility, which separates me from myself (from the ‘me’ that is mastery and power, from the free, speaking subject) and reveals the other in place of me, requires that I answer for absence, for passivity. It requires, that is to say, that I answer for the impossibility of being responsible - to which it has always already consigned me by holding me accountable and also discounting me altogether.”6 In their discussion on dispossession as the indication of the performative in the political, the philosopher Judith Butler and the anthropologist Athena Athanasiou emphasize too the Derridean claim that responsibility requires responsiveness, and consider self-poiesis as an (ethical) relational category which embraces self-care and self-crafting.7 “Responsibility is itself is a scene of political contestation”, so the authors contextualize the social situation of a responsive self and bring in a question of an ethical relation. “The politics of performativity entails an avowal of the power relations it contests and depends on; it encompasses ‘bearing responsibility,’ as it were, for the power configurations in which and through which we respond to each other.”8 Linking dispossession - a troubling concept which constitutes the processes of subjection - with disposition, as a presumed readiness towards the other, Butler and Athanasiou reflect upon what makes the political and ethical responsiveness possible: “The condition of dispossession - as exposure and disposition to others, experience of loss and grief, or susceptibility to norms and violences that remain indifferent to us - is the source of our responsiveness and responsibility to others. Performativity attends to precarity, then. It works to heed the claim of precarious life, through responsiveness, understood as a disposition toward others. In fact, ‘disposition’ - with all its implications of affective engagement, address, risk, excitement, exposure, and unpredictability - is what brings performativity and precarity together.”⁹ Disposition in a world of decline becomes a moral obligation, a duty; it too constitutes an act of resistance in precarious life on the search for collectivity and belonging. The world is gone. I must carry you.

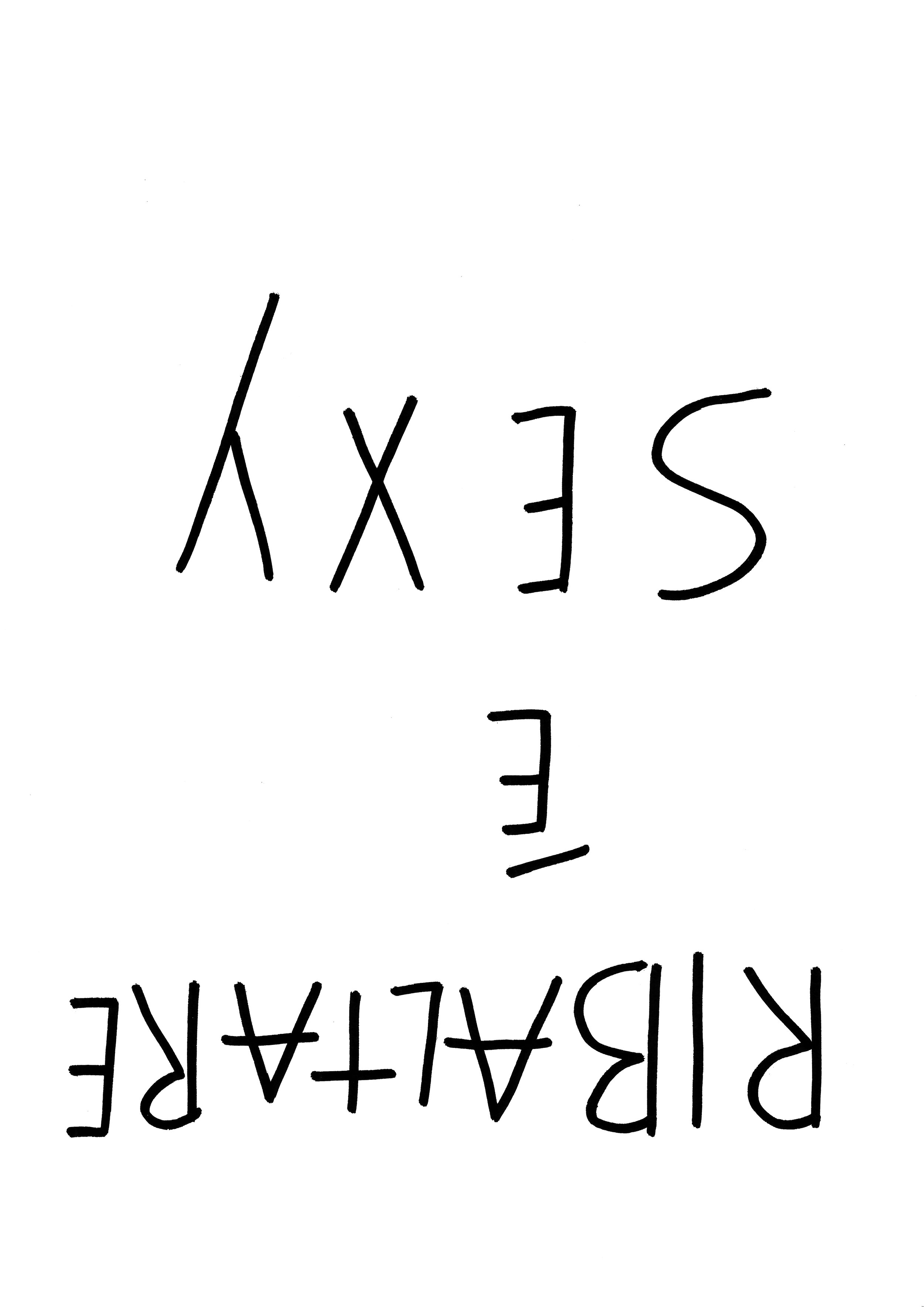

Paul Celan suggests “a breath” and “a name” as formative gestures of the world we are responsible for; the elemental acts of breathing and naming indicate a genuine political stance of subjects and communities. Naming raises questions of identity, legitimacy, matters of inheritance and signature. Breathing, a breath: the first one and the last one, and their continuous unfolding; the beginning and the end, and the in-between, life itself, and death, its companion. A resistance, an endurance, a resilience.

“We embraced each other by our names”, thus the philosopher of the French Renaissance Montaigne defines friendship in his legendary essays. In a study on naming in Jacques Derrida’s and Emmanuel Levinas’ philosophy, the theorist Christian Moraru argues that “names are […] no longer ‘metonymies’: they do not just ‘stand for’ what they name, for particular identities. Names constitute, ultimately are identities. The name has become its own, living referent, flesh and blood, body.”10 Naming is reinforcing; it is an instrument of both coercion (marking the destinies of the characters) and freedom (providing new possibilities for liberation). Derrida thoroughly analyses the paradoxes of naming, pointing out traditional “the name of the father” being perceived as the epitome of oppression as well as considering the naming’s ability to exceed the language and its power to disrupt the hegemony (a bold act of making a name for themselves, like the case of the builders of the tower of Babel). Similar ambiguity concerns Derridean understanding of a name as a gift. Analyzing the act of nomination in Jean Genet’s writing, the philosopher observes that “when Genet gives names, he both baptizes and denounces. (…) There is no purer present, no generosity more inaugural” in offering somebody the gift of name. Giving somebody a name is giving him/her “nothing, no thing, yet such a gift appropriates itself violently, harpoons, ‘arraigns’ [arraisonne] what it seems to engender, penetrates and paralyzes with one stroke [coup] the recipient thus consecrated.”11 Naming gains an ethical performative stance. In another text, Derrida realizes that the gift of name(s) can be corrupted; a name can make the person disappear, it can make him “drowned in the waters of his name, in which everything is engulfed”.12 He concludes in “Glas”: “to give a name is always, like any birth (certificate), to sublimate a singularity and to inform against it, to hand it over to the police.”13 As such, with its polyvalent nature, the naming is considered a powerful weapon as a political category of a visibility which contributes to the politics of recognition. Butler and Athanasiou appreciate a recognition as an empowerment and a transformative condition which enables a constant reinvention of new forms of political subjectivity. The authors emphasize: “one of the most crucial challenges that we face today, both theoretically and politically, is to think and put forward a politics of recognition that addresses, questions, and unsettles the common perception of the state or other apparatuses that monopolize power as natural mechanism of recognition.”14

In “The Meridian”15 Paul Celan defines the poetry as “a turn-of-breath”. “Who knows, perhaps poetry travels its path - which is also the path of art - for the sake of such a breath turning?”16, the poet adds. A spinning weal of breath is the cycle of life and death, its necessary “accessory”. Derrida points out the breath’s primacy: “without breath there would be neither speech nor speaking, but before speech and in speech, at the beginning of speech, there is breath.”17 Italian philosopher Franco “Bifo” Berardi confirms this thesis. For him, the breath and our contemporary condition of breathlessness consider the metaphor of poetry as the only line of escape from suffocation. 18 Poetry understood as “the excess of semiotic exchange” has gotten the power to reactivate breathing, thus to emancipate and self-empower. “Bifo”’s word play of in-spiration, re-spiration and con-spiration, concluding with expiration, foregrounds the breathing’s life-long ruling master narrative, its poetical rhythm (after Hölderlin) as well as its political tempo that orchestrates the breathing’s scope between the spasm, suffocation and death, the ultimate gesture of living. A devastating cry for help, “I can’t breathe”,19 uttered by a victim of the police brutality and extreme violence, became a massive chant of resistance and protest in solidarity, enacted by millions of demonstrators all over the globe. The impossibility to breathe - the breathlessness - began to signify the oppression and injustice, the uttermost abuse of power and aggression. The political turmoil overlaps with the current pandemic crisis, which affects our immunological system and the respiratory condition, and exposes vulnerability of our organisms. The restrictions necessary to prevent the spread of a deadly virus impact our individual and collective behavior and a way of acting towards the other, raising the social responsibility as well as reawakening our awareness of the natural environment which surrounds. We are in this together as the elemental gestures of breathing and touching become the possible threats. The frailty of the nature(s) has been drastically uncovered; in such troublesome times of uncertainty, resilience appears as a way to challenge the precarious situation and test a basic solidarity, necessary to obey the “new normal” of the communal practice. The distance between you and me is carefully measured; the breathing in and out is under a rigorous control as social distancing and isolation become a new collective fate and a new law of social relation. The ecology of others receives its new unexpected meaning. In a recent conversation, Franco “Bifo” Berardi links the outbreak of the pandemic with the unrest in America, providing a solution to the current situation of a psycho-physical and political impasse: “In my opinion, the explosion is showing a possible way out from the protracted lockdown and a possible form of respiration of the suffocating American society. Insurrection, permanent insurrection, is the only way to breathe. It is the only way to avoid a deep psychological depression in the coming months and years (…) How can we come out from this claustrophobia? How can we tolerate the violence of the police? The protests are exposing young people to the virus, that’s true. But inaction would expose them to a tunnel of depression and suicidal urges in the alternative future. The American insurrection is an answer to this question. Only insurrection can save us from a long-lasting depression.”20

Elaborated and conducted at the time of writing, on the stage of the world in an all-encompassing, unprecedented crisis and disarray, the 7th Biennale Gherdëina has stood out proud and vigorous as an unbeatable force that appropriated the (“insurrective”) affirmation as a possible strategy to deal with the present moment of uncertainty and suspense. “I call to actively embrace (this) ethic of affirmation.”, Rosi Braidotti proclaims as if prophetically in her manifesto-like statement, “We need to borrow the energy from the future to overturn the conditions of the present. It’s called love of the world. (…) Picture what you don’t have yet; anticipate what we want to become. We need to empower people to will, to want, to desire, a different world, to extract – to reterritorialize, indeed – from the misery of the present joyful, positive, affirmative relations and practices. Ethics will guide affirmative politics.”21 Affirmation is a situated and relational, ethical praxis which relies upon the sense of collective responsibility and care as well as a belief that negative affects can be transformed. As such, it disregards the dualism of self/other, and all other binary oppositions, including nature/culture and human/non-human. We are in this together, the philosopher reminds, as the approach she advocates assumes a relationality on all sides and proposes a more egalitarian relationship to and between the species. Developed along the vectors of affirmation, Braidotti’s Spinozian political economy of subjectivity is a therapeutic tool for our post-human, post-anthropocentric times of a zoe-geo-techno bound, ecological grounded and technologically mediated. Addressing the politics of ecology and the urge to decolonize nature within the fields of arts, activism and environmental studies, an art historian and cultural critic T. J. Demos acknowledges these thoughts’ influence on contemporary art and activism: “for Braidotti, this ‘becoming-Earth’ movement offers a ‘new transversal alliance across species and among post-human subjects which opens up unexpected possibilities for the recomposition of communities, for the very idea of humanity and for ethical forms of belonging’. (…) These activist-artistic practices also figure as forms of social engagement, collective mobilization in public space, and ambitious proposals for a different natural-cultural world today, as well as the reinvention of contemporary art.”22 Our world’s alarming state of emergency derails humanity from any safe zone, demanding an urgent action of an all-encompassing scale. As a Cameroonian philosopher and political theorist Achille Mbembe defines the necessary task, updating the understanding of the worldmaking: “If, indeed, Covid-19 is the spectacular expression of the planetary impasse in which humanity finds itself today, then it is a matter of no less than reconstructing a habitable Earth to give all of us the breath of life. We must reclaim the lungs of our world with a view to forging new ground. Humankind and biosphere are one. Alone, humanity has no future. Are we capable of rediscovering that each of us belongs to the same species, that we have an indivisible bond with all life? Perhaps that is the question – the very last – before we draw our last dying breath.”23

===========================================================================================================================

After From Here to Eternity (2016) and Writing the Mountains (2018), the last and concluding chapter of a trilogy on the politics of belonging arrives to Val Gardena under a title - a breath? - a name? the ways of worldmaking (2020). In the 7th edition of the Biennale Gherdëina, all previously featured thematic fields - the significance of the cultural legacy, the research of historical strategic positioning, the praise of the communal, the omnipresence of the nature and its “industry” - receive a social and political framing with no ignorance to the poetic, the spiritual and the existential, thus further unfolding the complexity of the vernacular language with an attention paid to the continuity and perseverance of tradition, its necessary rewriting and undoing as well as its transformative potential. The biennale focuses on the importance and the awareness of a political gesture in an active process of worldmaking, on its dynamic factor that guarantees a resilience of culture and nature, shapes the emancipated vernacular uniqueness of a place and manifests a brave, mature vision of a future to come.

Three chapters on sociology of an encounter and the politics of the plural constitute the core of - a breath? - a name? the ways of worldmaking: ecology of others - on reinvigorating the relationality (following a French anthropologist Philippe Descola’s reflection upon the nature-culture binary), in praise of hands - on the craft of touch (enhanced by a French art historian Henri Focillon’s dream of art’s autonomy within the domains of materials, techniques and signs) and the cloud of possibles - on dissemination of enthusiasm and the power of differentiation (referring to an Italian sociologist and philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato’s shift from capital-labour to capital-life). The notions of responsibility and humility connect all three chapters in an attempt to define the agencies of responsiveness and care, the main challenges in today’s active process of worldmaking.

—

1 Nelson Goodman, Ways of Worldmaking, The Harvester Press, p.3-6 (originally published 1978).

2 Olga Tokarczuk, Nobel Prize in Literature Acceptance Speech, 20189

3 A term elaborated by Achille Mbembe in: Ethics of the Passerby, published in: Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics, Duke University Press 2019

4 Paul Celan, Tabernacle Window, in: Die Niemandsrose, 1963

5 Jacques Derrida, Sovereignities in Question. The Poetics of Paul Celan, Perspectives in Continental Philosophy Fordham University Press New York 2005, p. 33

6 Maurice Blanchot, The Writing of the Disaster, University of Nebraska Press 1986, p. 25

7 Judith Butler and Athena Athanasiou, Dispossession: The Performative in the Political, Polity Press 2013, p. 66

8 Judith Butler and Athena Athanasiou, op. cit., p. 104

9 Judith Butler and Athena Athanasiou, op. cit., p. 105

10 Christian Moraru, We Embraced Each Other by Our Names: Levinas, Derrida and the Ethics of Naming, in: Names 48, no. 1, 2000, p. 49–58

11 Jacques Derrida, Glas, University of Nebraska Press 1986, p. 6

12 Jacques Derrida, Pas, p. 98

13 Jacques Derrida, Glas, op. cit., p. 7

14 Judith Butler and Athena Athanasiou, op. cit., p. 83

15 Paul Celan, The Meridian, originally presented as a speech to the German Academy for Language and Poetry on the occasion of Celan’s acceptance of the Georg Büchner Prize for Literature, 1961

16 Paul Celan, The Meridian, in: Jacques Derrida, Sovereignities in Question. The Poetics of Paul Celan, op. cit., p. 180

17 Jacques Derrida, Sovereignities in Question. The Poetics of Paul Celan, op. cit., p. 110

18 Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Breathing. Chaos and Poetry, semiotext(e) intervention series n. 26, 2018

19 “Bifo” mentions “I can’t breath” in relation to African American Eric Garner’s assassination which occurred on July 17, 2014 in Staten Island, NYC, when a NYPD officer put him in a chokehold for about fifteen to nineteen seconds while arresting him. A similar act of police violence and an identical cause of death occurred on May 25, 2020 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. A white police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on the neck of yet another African American man, named George Floyd for a period initially reported to be 8 minutes and 46 seconds, causing his death. In both cases, the victims uttered “I can’t breath”.

20 Franco “Bifo” Berardi in a conversation with Deja Crnović, June 22, 2020 in: https://www.disenz.net/en/franco-berardi-bifo-permanent-insurrection-is-the-only-way-to-breathe/

21 Rosi Braidotti, Borrowed Energy. Timotheus Vermeulen talks to philosopher Rosi Braidotti about the pitfalls of speculative realism in Frieze 165, August 12, 2014: https://www.frieze.com/article/borrowed-energy

22 T. J. Demos, Decolonizing Nature. Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology, Sternberg Press 2016, p. 242

23 Achille Mbembe, The Universal Right to Breathe, Critical Inquiry, April 13, 2020 in: https://critinq.wordpress.com/2020/04/13/the-universal-right-to-breathe/